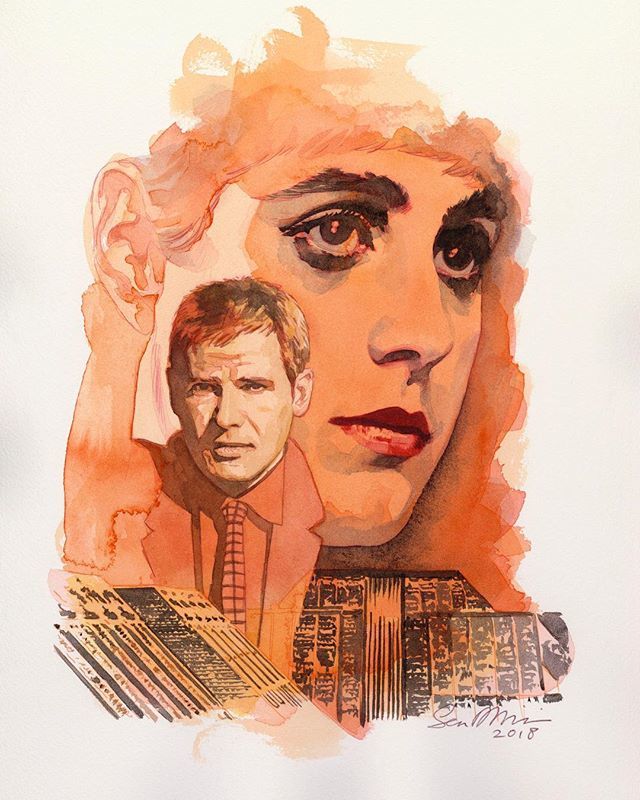

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears…in…rain. Time to die.”

Rutger Hauer

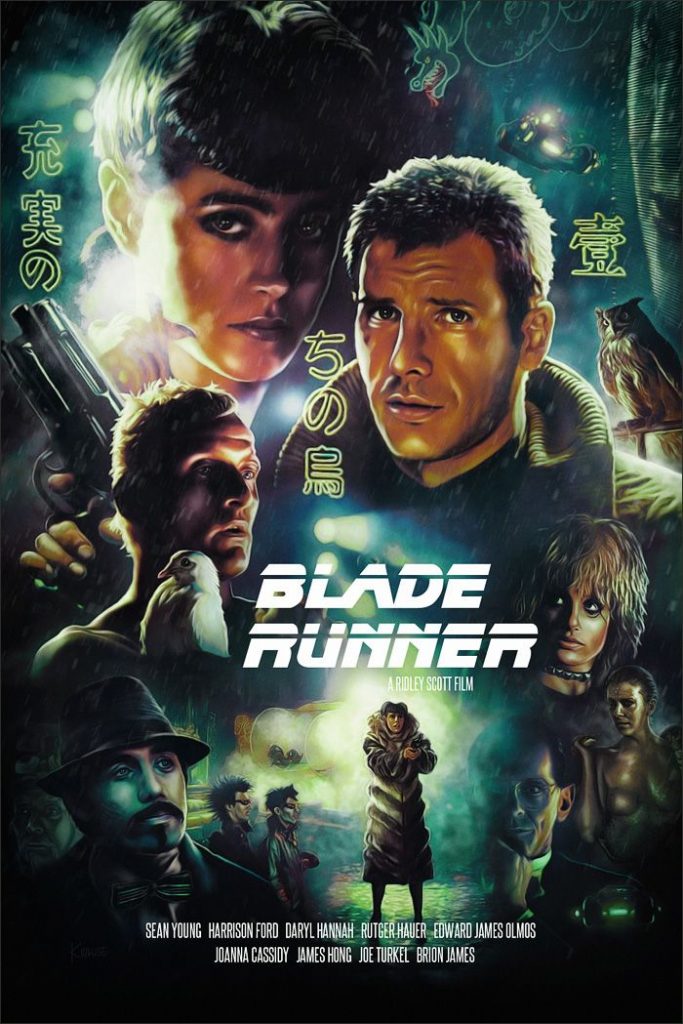

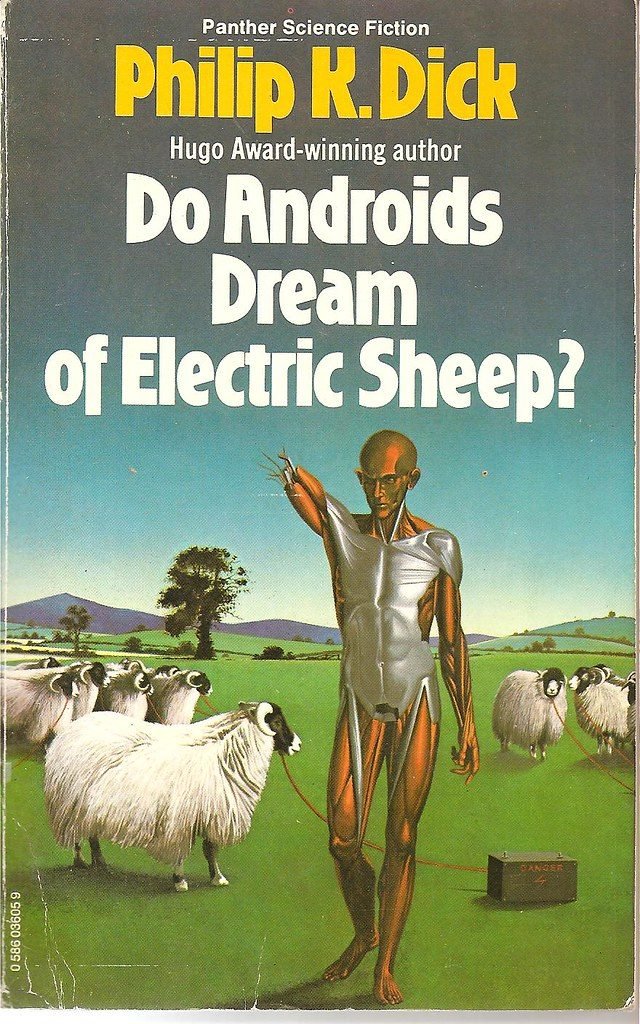

If we should attempt a DNA ancestry test of Blade Runner, the result would probably show an aesthetic lineage going back from the side of the first parent to the film noir, depicting the crime drama with the black and white visuals and the hard-boiled school of the American crime fiction and from the side of the second parent back to three generations of sci-fi literature: the so called “Hard” sci-fi of the ‘30’s, the sociological sci-fi of the ‘50’s and the “New Wave” which included authors as Delany, Ballard and Moorcock and arose as a style in literature during the 1960’s; the important aspect of science fiction as a genre of socio-psychological concern differentiates “New Wave” from its predecessors. Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), stands out as an excellent example of the New Wave era and it inspires Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner which hits the cinema screens in June 1982. The film is one of the few in the history of cinema that can be characterized as a work in progress as there are seven versions with the first being the “Theatrical” (1982) and the last, the “Final Cut” (2007) (https://bladerunner.fandom.com/wiki/Blade_Runner_versions).

Blade Runner’s summary plot

In the movie, Harrison Ford stars as Rick Deckard, a retired cop in Los Angeles circa 2019. L.A. has become a pan-cultural dystopia of corporate advertising, pollution and flying automobiles, as well as replicants, human-like androids with short life spans built by the Tyrell Corporation for use in dangerous off-world colonization. Deckard’s former job in the police department was as a talented blade runner, a euphemism for detectives that hunt down and assassinate rogue replicants. Called before his one-time superior (M. Emmett Walsh), Deckard is forced back into active duty. A quartet of replicants led by Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) has escaped and headed to Earth, killing several humans in the process.

The Socio-psychological aspect of the narrative

In both Blade Runner and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the protagonist upon accomplishing his mission, has the opportunity to reconsider his humanity/human identity. In the novel he has the choice to retain his memories or to delete and reprogram himself; in the film it’s insinuated that he himself might be an android. The outcome of the quest is therefore the radical undermining of self-identity masterminded by a mysterious, all-powerful agency, the Tyrell Corporation, which succeeded in fabricating replicants unaware of their replicant status, i.e., replicants misperceiving themselves as humans.

According to Slavoj Žižek, the world depicted in the film as a metaphor, is the world in which the corporate Capital succeeded in penetrating and dominating the very fantasy kernel of our being: none of our features is really “ours”; even our memories and fantasies are artificially planted. Thus the fusion of Capital and Knowledge (Tyrell Corp.) brings about a new type of proletarian (replicant) who’s deprived of a private personal identity so that what remains is now literally the void of pure substanceless subjectivity (Slavoj Žižek, Tarrying with the Negative. Kant, Hegel and the critique of ideology). A relevant problematic will be explored in sci-fi cinema later on with films such as Alex Proyas’ Dark City (1998) Joseph Rusnak’s The 13th floor (1999), and Wachowskis’ sisters The Matrix (1999).

Cyberpunk: the world of Blade Runner

Blade Runner alongside two other films that came out in 1982, Steven Lisberger’s TRON and David Cronenberg’s Videodrome, were also the predecessors of a new sci-fi subgenre, Cyberpunk, which proved to be a true revitalizing art force. It will be defined stylistically on 1984 with the publication of William Gibson’s Neuromancer and although the movement almost ended as soon as it began in it’s literary form, its impact has been felt, and its techniques absorbed, across a range of media and cultural formations (Scott Bukatman, Terminal Identity – The virtual subject in postmodern science fiction).

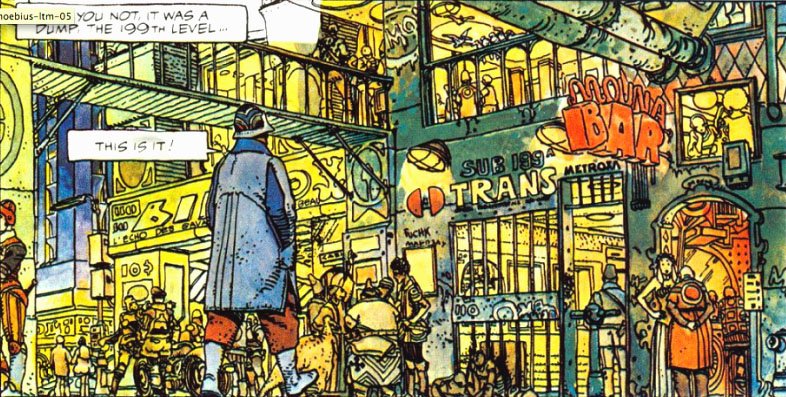

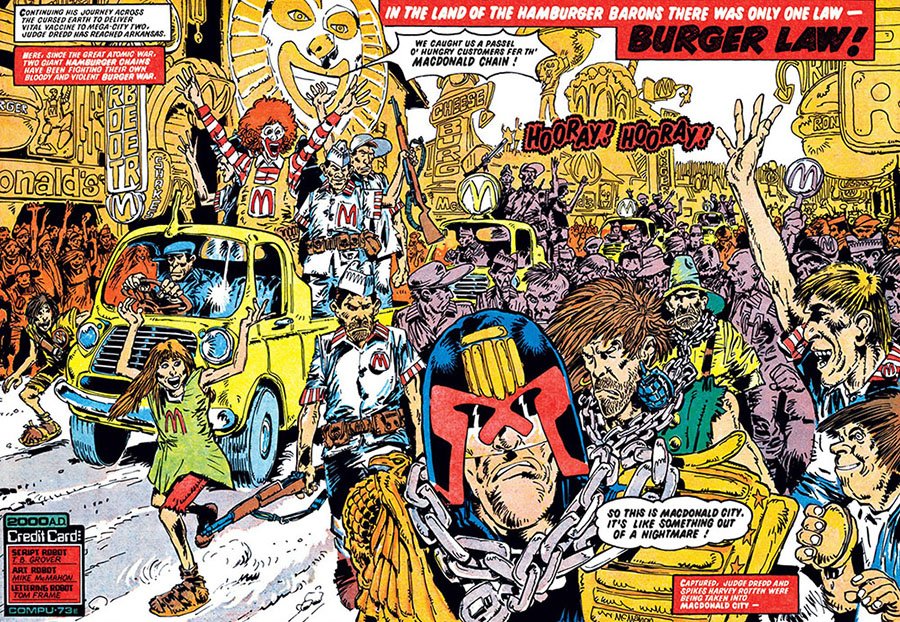

Blade Runner’s future Los Angeles quoted the comics: the crowded urbanism of Moebius (Jean Giraud) who in the pages of Heavy Metal magazine created influential images of cities without top, without bottom, without limits. It also quoted Judge Dredd and Ranxerox. The film’s dystopian futuristic setting that tends to focus on a combination of “high-tech and low life”, features advanced technological and scientific achievements, such as artificial intelligence and cybernetics, juxtaposed with a degree of breakdown or radical change in the social order.

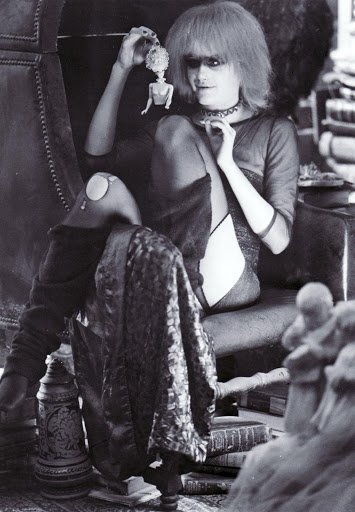

The existence of androids in Blade Runner’s dystopian society takes a central point in the films problematic. On the one hand, we view the replicants with awe and wonder: they are the ultimate toys, pets, servants and lovers. They are the ideal children or parents or mates we wish we had, the perfect replications of ourselves.

On the other hand, androids and robots are projections of our fears concerning dehumanizing technology run rampant and scientific creations out of control. The replicant as a double (Doppelgänger), even if it seems intimate and familiar, it becomes ambivalent until it finally comes to mean its opposite: the Freudian uncanny, something strange and unfamiliar, even threatening (Joseph Francavilla, The Android as Doppelgänger).

Blade Runner aesthetics: the image

Apart from Ridley Scott’s artistic vision it is difficult to imagine the film without Syd Mead’s designs, Douglas Trumbull’s special effects, Jordan Cronenweth’s exceptional cinematography and Vangelis’ marvelous score.

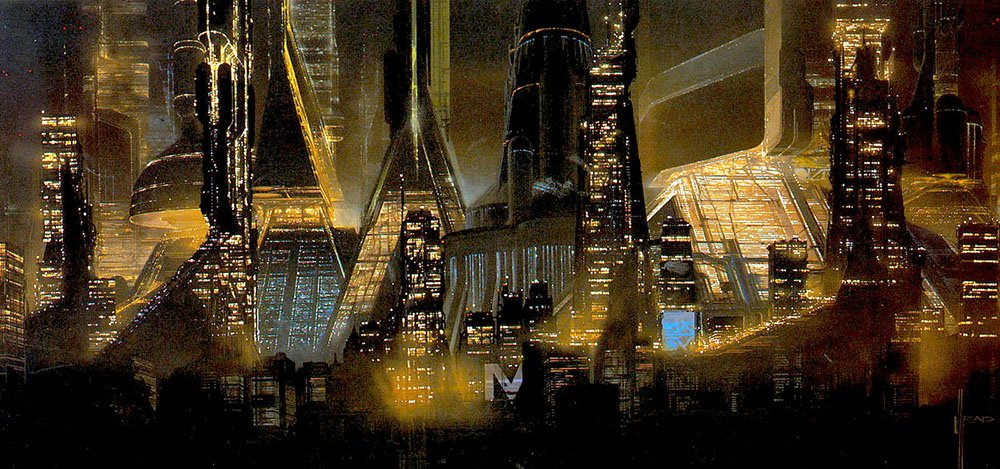

Syd Mead, as Ridley Scott used to say, was “this wonderful combination of artist and practitioner and sociologist. He can talk for hours about the logic of urban planning, urban decay and sociological decay and disorder” (Andrew Abbott, On the edge of Blade Runner). His futuristic and realistic designs gave birth to the film’s truly believable 2019 Los Angeles as every aspect of the city was extremely well thought of and executed to the very last detail.

The film’s noir conception needed to evoke romanticism and urban chaos; the photography had to create a pervasive claustrophobia and thus all the interior sets on Blade Runner had ceilings. Cronenweth’s characteristic method, involved combining a soft frontlight, with a hard backlight, creating intense silhouettes and haloes.

The addition of smoke or reflective effects in the background further abstracted the space. The end results were crisp while remaining hazy and glamorous. The street scenes were often shot with a hand-held camera using the available light of the neon signs which were everywhere in the set (Scott Bukatman, Blade Runner).

With the creation of Blade Runner’s city all boundaries between public and private are rejected: Beams of light strafe the innermost recesses of apartments and alleys. Cronenweth said that the lights were used “for both advertising and crime control, much the way a prison is monitored by moving search lights. The shafts of light represent invasion of privacy by a supervising force, a form of control. You are never sure who it is…” (Lightman and Patterson, Production Design).

In this dystopian totalitarian reality the architecture evolves with a class hierarchy from bottom to top. As Mead comments: “[…] in my design […] mind that, with these enormous structures going up to 2000-3000 feet, descent people never went bellow the 60th floor, so you’d got these pylons supporting the architecture and the street then became like a basement essentially, an urban basement…” (Andrew Abbott, On the edge of Blade Runner).

Blade Runner aesthetics: The sound

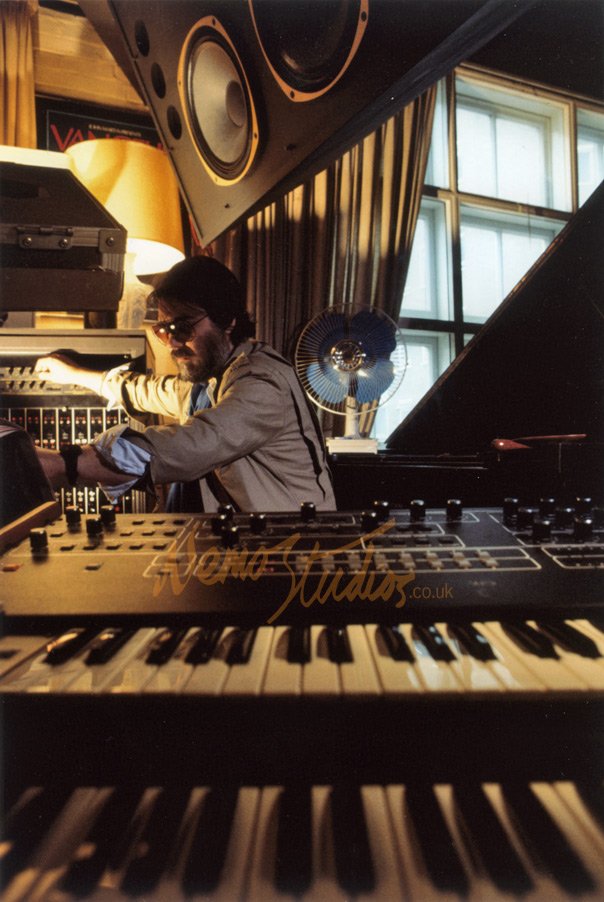

Blade Runner finds the Greek composer Vangelis Papathanasiou at the top of his game. Having already won an Oscar award for his music in H. Hudson’s historical drama Chariots of Fire (1981), with a main theme that nowadays finds itself among the cinema’s all time classics, he accepts the challenge to score Blade Runner and he does so letting his music play a vastly different role in this one. Having his signature under 99% of the film’s music (the 1% being Gail Laughton’s Harps of Ancient Times for the bicycle riders scene and Ensemble Nipponia’s Ogi no Mato) he achieves a fusion between the sound and the image, he sets the mood of each scene and uses the new technological means of the epoch (such as the digital reverb Lexicon 224) to incorporate the sound of the environment into the music and vice versa.

I’d say that there are four stylistic elements in Vangelis’ score, which are masterfully connected:

1.The jazzy/bluesy background reeking lust and nostalgia that we usually find in film noir. The scene where J.F. Sebastian finds Pris among the trash, or the love scene between Deckard and Rachael or even when he reveals to her that she is a replicant.

2.The futuristic electronic, synth based sound, appropriate for Sci-Fi films. Opening of the film, the eerie music and bass-synth drones that come and go during the unicorn scene or during the battle between Deckard and Batty, the ending titles.

3.The orchestral-inspired dramatic climaxes. Tyrell’s death scene where the music signals a Wagnerian culmination or the Beethovenian heroic death of Roy Batty.

4.The “diegetic music” that’s in the story and part of the drama rather than behind it. A striking example is when the music reflects city-speak; a mixture of words and expressions from Spanish, French, Chinese, German, Hungarian and Japanese that Gaff and Deckard speak in the beginning of the film. The musical analog can be heard when Deckard tracks down Zohra through the red light district with the Hispano/Japanese pop playing in the background, or later when he enters the night club where we hear that mixture of Arabic and western electronic beat music (Andrew Stiller, The Music in Blade Runner).

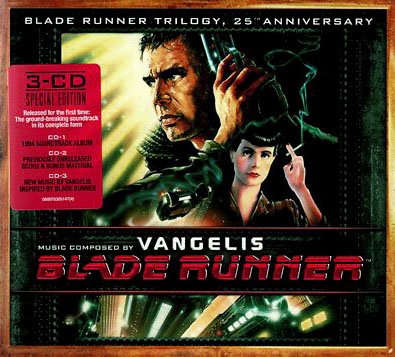

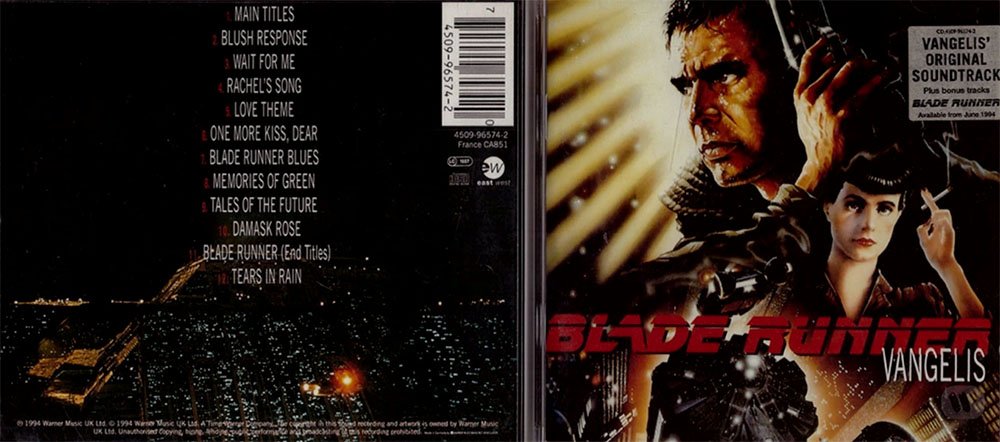

In 1994 and after many non-official leaks, we have the film’s soundtrack signed by Vangelis as a CD release with 12 tracks released by East West (Warner Music) in the UK and by Atlantic Records in the US. An interesting thing that we understand after this long awaited release is that Vangelis had composed the music for Blade Runner as a suite, as one of his own studio material that could be (or was it meant to be?) heard as an independent audio release. In the film we hear a portion of the music that we get on the CD which has a total running time of about 58min, and at the same time we don’t get to hear all of the score as there are parts missing.

In 2007 there was a 3 disc CD version of the soundtrack that came to correct some of the aforementioned issues. The first disc is a beautifully remastered version of that 1994 version and that’s great as far as it goes, but it still doesn’t address the missing final score. Disc two is the real treasure, though, because it contains a lot more of the score’s original music. There’s the awesome music that plays in the film while Deckard and Roy have their final near mythic battle to the death in the rain. Likewise, the music for the investigation of “Leo’s Room” is included here, as is the subtle, deeply moving composition for the death scene of Dr. Tyrell. There are also a couple of “bonus tracks” that fill out some missing music in the film. The third and final disc is made up of some synth sketches, ideas, and asides, and little more. There is a gimmicky bit where Vangelis takes on Scott’s dialogue about the Final Cut version of the film and layers his keyboards over it (Thom Jurek, Blade Runner Trilogy: 25 Anniversary).

The films musical impact

Vangelis’ music on Blade Runner had a huge impact in the electro scene admittedly on artists such as Hans Berg, Gary Numan, Ikonika, Abayomi, Kuedo, Stuart Braithwaite, Hans Berg, Bjork and more. Perhaps the reason for this close connection between Blade Runner and the evolution of the electronic music especially, could be found in the core of the film’s theme: A story about the ambivalent relationship between man as a creator and machine as a creation, the role of the latter influencing-forming and henceforth decisively determining the conditions for the existence of the former. This dialectical contradiction seeks to be overcome through the transition to a new situation where man seeks through the use of the machine a “more human than human” condition. And what could be a more appropriate artistic analogue than electronic music, a genre where the musician is summoned to express his emotional and aesthetic complexity by using in essence electronic means, the “true” nature of which (in the sense of the precise internal functions and technology or the principles of construction) he ignores, but nevertheless they are the means to his phycological and mental fulfilment through the artistic procedure.

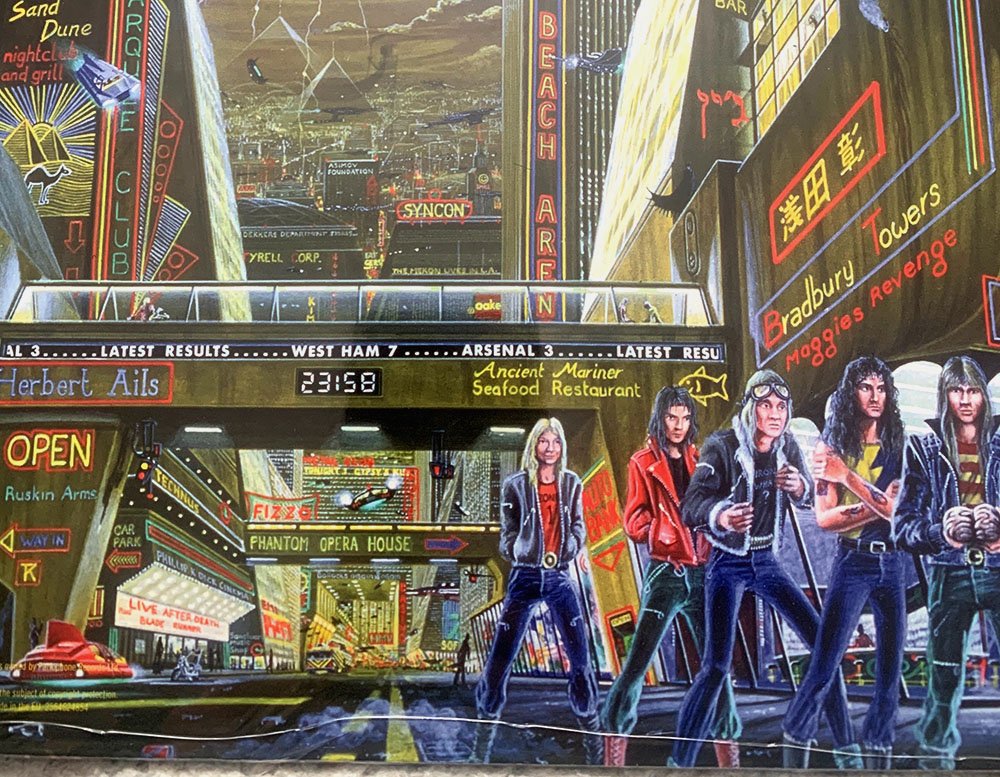

But pop, rock and even heavy metal music wasn’t left untouched by the films aesthetic influence; The Stranglers had a track named Time to Die and Therapy? a track called Meat Abstract but let’s stay to our closest musical relatives: On the back cover of Iron Maiden’s 1986’s masterpiece “Somewhere in Time” we read on the movie theater, which is called the Philip K. Dick Cinema: “Live After Death – Blade Runner”, right behind the bridge, which runs the “latest results… West Ham 7…” there’s a building with the sign “Tyrell Corp.” grab your LPs and your magnifying glasses! And of course from Blind Guardian’s Somewhere Far Beyond (1992) album there’s the opening track called Time, What is Time?.

And quoting a part of its beautiful lyrics I’d like to close my article:

Look into my eyes

Feel the fear just for a while

I’m a replicant and I love to live

Is it all over now

Only these years

I’ll leave but I’m singing…

Yiannis Tziallas

Related Link: Yiannis Tziallas – Official Page